Hello everyone, in this series we are going to discuss step-by-step methodology you can follow when attacking a web application. The methodology is presented as a sequence of tasks that are organized and ordered according to the logical interdependencies between them. Information gathered in one stage may enable you to return to an earlier stage and formulate more focused attacks. For example, an access control bug that enables you to obtain a listing of all users may enable you perform a more effective password-guessing attack against the authentication function or a file disclosure vulnerability may enable to you perform a code review of key application functions rather than probing them in a solely black-box manner.

Map the application content

1: Explore visible content

1.1: Configure your browser to use your favorite proxy tool. I used to use Burp Suite to monitor and parse web content.

1.2: Browse the entire application in the normal way, visiting every link and URL, submitting every form, and proceeding through all multistep functions to completion. If the application uses authentication, and you have or can create a login account, use this to access the protected functionality.

1.3: As you browse, monitor the requests and responses passing through your intercepting proxy to gain an understanding of the kinds of data being submitted and the ways in which the client is used to control the behavior of the server-side application.

1.4: Run passive spidering using burp suite to identify any content or functionality that you have not walked through using your browser.

2: Use internet search engines

2.1: Use advanced search options to improve the effectiveness of your research. For example, on Google you can use site: to retrieve all the content for your target site. Check the Maximize Search Results post.

2.2: Perform searches on any names and e-mail addresses you have discovered in the application’s content, such as contact information. Include items not rendered on-screen, such as HTML comments.

2.3: Look for any technical details posted to Internet forums regarding the target application and its supporting infrastructure.

3: Discover hidden content

3.1: Confirm how the application handles requests for non-existent items. Make some manual requests for known valid and invalid resources, and compare the server’s responses to establish an easy way to identify when an item does not exist.

3.2: Try to understand the naming conventions used by application developers. For example, if there are pages called AddDocument.jsp and ViewDocument.jsp, there may also be pages called EditDocument.jsp and RemoveDocument.jsp.

3.3: Review all client-side code to identify any clues about hidden server-side content, including HTML comments.

3.4: Use automation to discover more content. There are two great tools that can help you with this stage, dirbuster and dirsearch. For me , I prefer dirsearch.

4: Enumerate Identifier Specified Functions

Identify any instances where specific application functions are accessed by passing an identifier of the function in a request parameter (for example, /admin.jsp?action=editUser or /main.php?func=A21. If the application uses a parameter containing a function name, first determine its behavior when an invalid function is specified, and try to establish an easy way to identify when a valid function has been requested.

5: Debug parameter

Choose one or more application pages or functions where hidden debug parameters (such as debug=true) may be implemented. These are most likely to appear in key functionality such as login, search, and fi le upload or download. Use listings of common debug parameter names (such as debug, test, hide, and source) and common values (such as true, yes, on, and 1). Iterate through all permutations of these, submitting each name/value pair to each targeted function. For POST requests, supply the parameter in both the URL query string and the request body. You can use the cluster bomb attack type in Burp Intruder to combine all permutations of two payload lists.

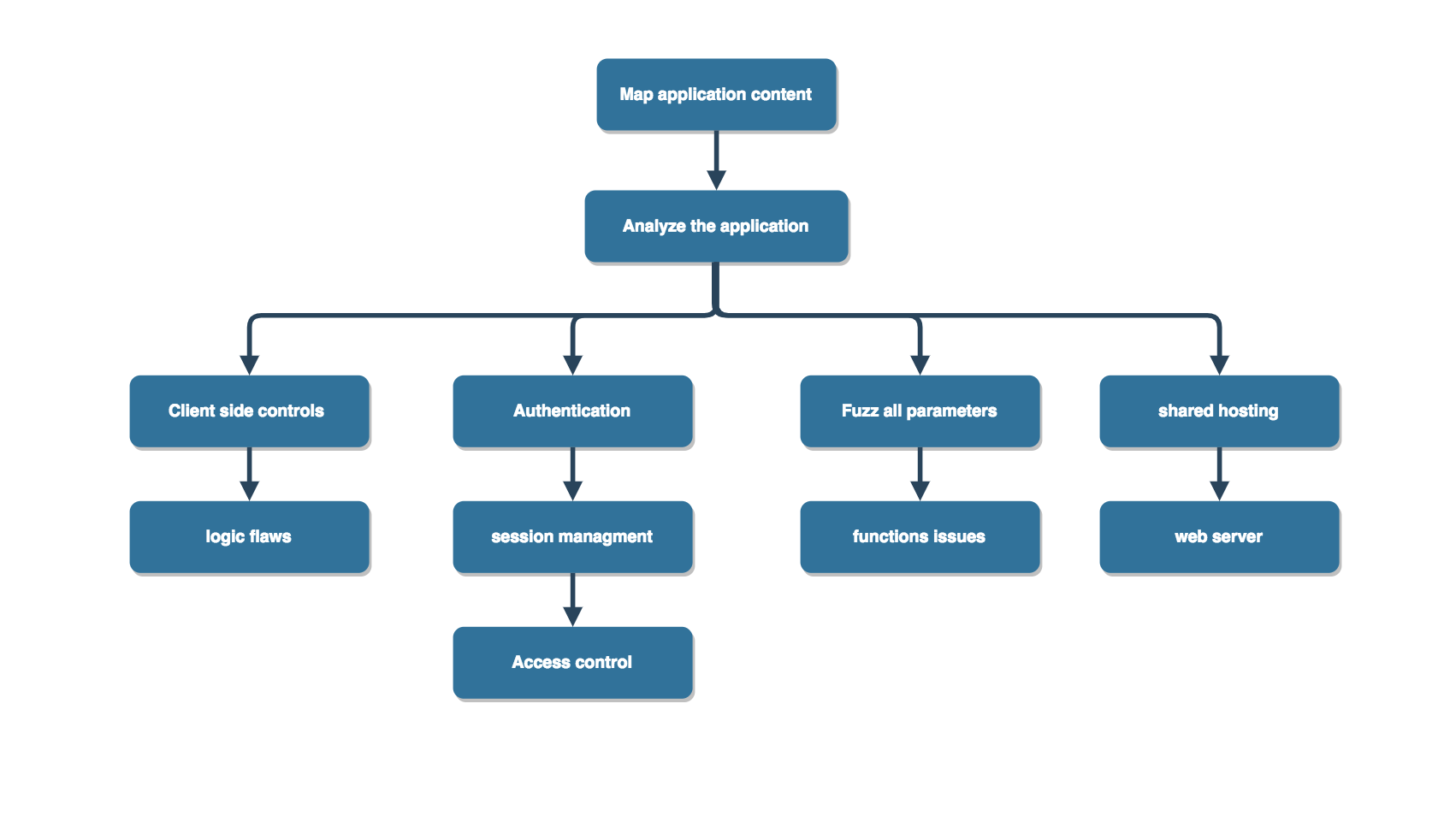

Analyze the application.

1: Identify the functionality

Identify the core security mechanisms employed by the application and how they work. In particular, understand the key mechanisms that handle authentication, session management, and access control, and the functions that support them, such as user registration and account recovery.

2: Data entry points

Identify all the different entry points that exist for introducing user input into the application’s processing, including URLs, query string parameters, POST data, cookies, and other HTTP headers processed by the application

3: Identify technologies

3.1: As far as possible, establish which technologies are being used on the server side, including scripting languages, application platforms, and interaction with back-end components such as databases and e-mail systems.

3.2: Check the HTTP Server header returned in application responses, and also check for any other software identifi ers contained within custom HTTP headers or HTML source code comments. Note that in some cases, different areas of the application are handled by different back-end components, so different banners may be received.

3.3: Review the results of your content-mapping exercises to identify any interesting-looking file extensions, directories, or other URL subsequences that may provide clues about the technologies in use on the server. Review the names of any session tokens and other cookies issued. Use Google to search for technologies associated with these items.

4: Map the Attack Surface

4.1: For each item of functionality, identify the kinds of common vulnerabilities that are often associated with it. For example, fi le upload functions may be vulnerable to path traversal, inter-user messaging may be vulnerable to XSS, and Contact Us functions may be vulnerable to SMTP injection.

4.2: Formulate a plan of attack, prioritizing the most interesting-looking functionality and the most serious of the potential vulnerabilities associated with it. Use your plan to guide the amount of time and effort you devote to each of the remaining areas of this methodology.

In the next part we are going to discuss the client side controls.